Catherine Spears Frye Carpenter

No actual photographs of Catherine SF Carpenter exist. Above is an AI-generated image based on facts known about her life.

“Resilient Bourbon Widow”

Catherine Spears was born in 1760 in Augusta County, Virginia. She grew up in a wealthy family headed by her prosperous father, George Spears. Catherine received education and training, which, for a non-city dweller, was then exceedingly uncommon. She became an expert at weaving, which was at that time a household industry forming the backbone of a woman’s necessary economic work.

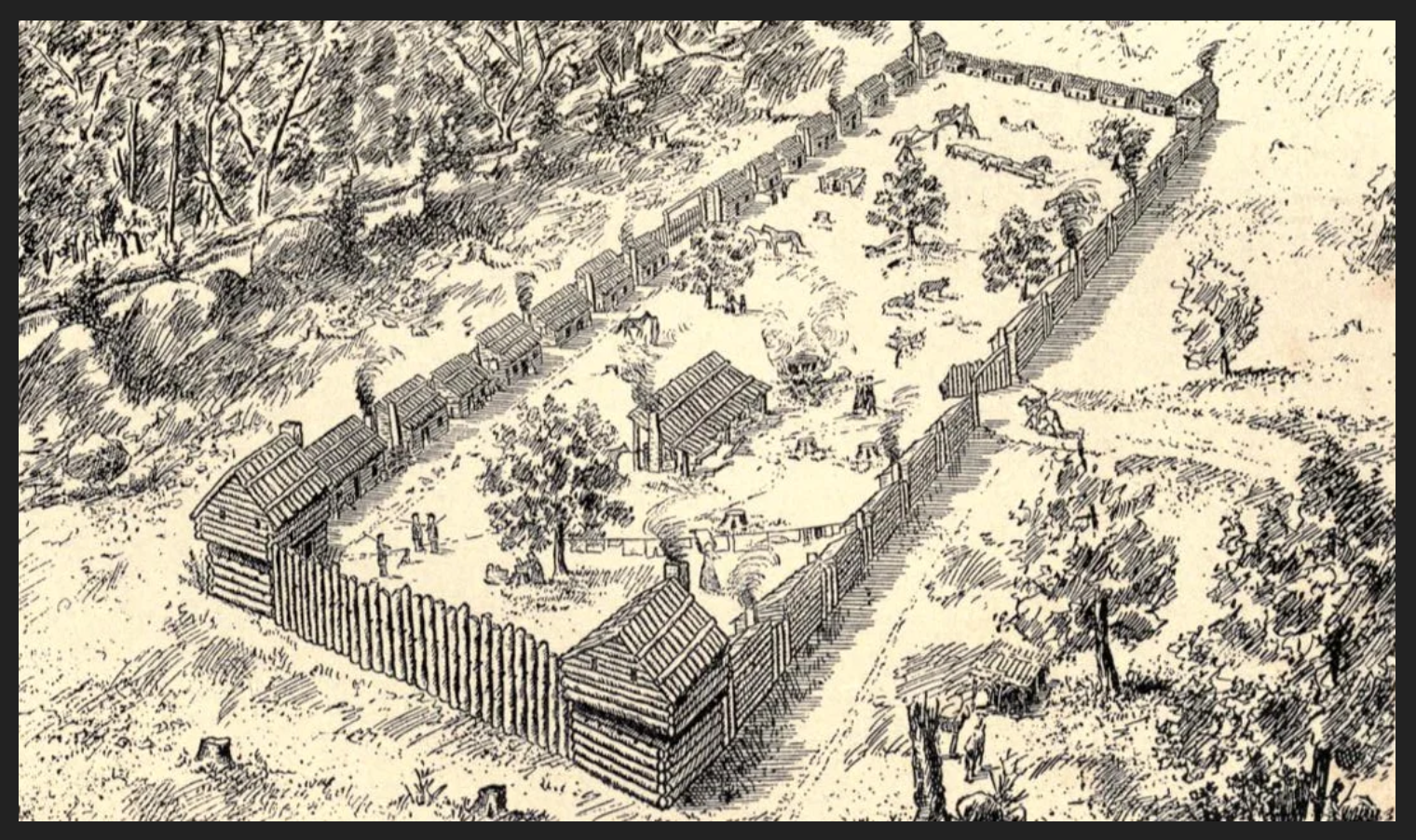

At 16, Katherine married John Frye, a fellow Virginian. Soon after, the pair followed kin and neighbors west into untamed Kentucky, joining a migration led by her brother-in-law John Carpenter and sister Elizabeth. By 1780, the group of families, including John and Catherine, clustered at what they later called Carpenter’s Fort, a wilderness settlement that stood on the modern-day Lincoln/Casey County line.

Fort Boonesborough, not Fort Carpenter, but an accurate illustration of a Kentucky wilderness settlement on which Fort Carpenter may have been based. Note families’ living quarters along the back wall. Settlers had to leave the safety of the fort daily for food and water and Native American attacks were frequent.

Late-18th-century frontier life brought hard tests. On August 19, 1782, during the Battle of Blue Licks, one of the last major battles of the Revolutionary War in Kentucky, John Frye was killed while serving in the militia. Catherine was left a 22-year-old widow, heavily pregnant with her second child, and with a small daughter already at home. A few weeks later she delivered John Frye, Jr., and in the difficult weeks that followed, necessity dictated that she go through the emotional and physical turmoil of administering her late husband’s will and managing his estate.

Two years later, in 1784, Catherine married Adam Carpenter (who was her neighbor and sister Elizabeth’s husband’s brother). Adam was one of the founders of the settlement of what was to become the small town of Carpenter’s Station, Kentucky, which still exists. Adam and Catherine’s blended family grew quickly, and Catherine ultimately raised twelve children, two from John Frye, and ten with Adam Carpenter. When Adam died in 1806, the now-46-year-old Catherine, twice widowed, was again left at the head of a complex frontier household, now even more so, with 667 acres of land, livestock, and labor to manage, including a slave boy named Joseph, who became the farm’s supervisor after Adam’s death.

Fortunately for Catherine, profitable whiskey-making had come to form an important part of her household economy in those years, linking her directly to Kentucky’s developing whiskey tradition. In 1815, she appears in county tax records paying “tax on 100 gallons of spirits distilled,” a fairly significant amount of whiskey for those days, and an indication that she was producing spirits at scale sufficient to be recorded (and taxed) by the state. Even more consequential is a surviving document from Catherine Carpenter’s papers at the Kentucky Historical Society (KHS), dated 1818, that preserves her instructions for both “sweet mash” and “sour mash” whiskey. Catherine’s recipe is one of the earliest recorded American examples of the method, predating the celebrated work of Dr. James C. Crow by many years, who, despite Catherine’s manuscript, is still credited for the “invention” of sour mash. In short, Catherine emerges not as a footnote to bourbon history, but as a groundbreaking single female entrepreneur who used distilling to support and stabilize a large frontier family unit.

Catherine’s whiskey, like that of many early Kentucky households, would have been distilled in and around the seasonal rhythms of farming. That is, utilizing excess corn not needed for food or for animal feed, mashing grain after harvest, fermenting when temperatures permitted, and redistilling as needed. The 1818 “Recipe for Distilling Corn Meal Sweet Mash” and the companion sour-mash instructions show a practical, repeatable process: proportions of meal and water, the use of backset, timings, and sensory checks. Written recipes from this era are rare; that hers survive gives readers a rare window into everyday frontier distilling as practiced by someone managing a large household as well as a rather substantial farm enterprise.

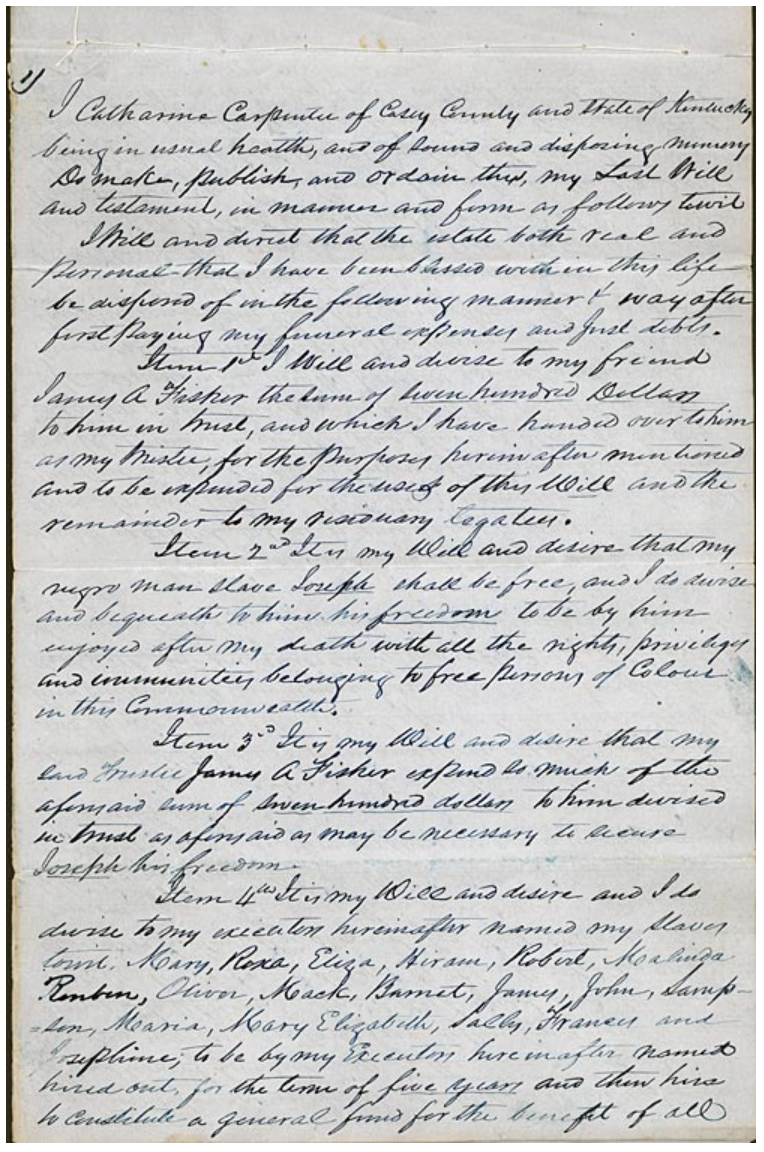

Catherine’s life story also reveals the contradictions of the period. The same will and family papers that illuminate her cutting-edge distilling and wise land management also document her participation in slavery and, late in life, her thoughts about emancipation. In a will dated May 27, 1846, Catherine made provisions concerning the people she enslaved, including her plans for emancipation. The document provides direct, unfiltered evidence of the legal and moral complexities that underwrote agricultural realities, and thus distilling, in antebellum Kentucky.

Catherine remained a central figure in the Carpenter’s Station area until her death at the age of 88 on April 1, 1848, in what was then Lincoln County, Kentucky. By the time she died, Catherine owned nearly five square miles of prime Kentucky farmland, which her son George managed until his own death in 1870. Catherine SF Carpenter was not a brand owner in the modern sense, and no distillery bearing her name survived into the age of industrial bourbon. But across the arc of her life, from a young Virginian bride on the move to Kentucky, to a pregnant widow after Blue Licks, to a twice-widowed farm manager who paid significant tax on her distilled spirits and then committed her methods to paper, she embodies the intertwined stories of frontier Kentucky and early whiskey making. Her recipe from 1818, now preserved in an archive, lets us read her process in her own terms. And that, perhaps, is the most valuable link. That is, between a woman’s arduous toil on the ragged edge of necessity, undergoing pitiless hardship, and surviving, in part, by employing craft traditions that would in a few decades would become bourbon, Kentucky’s most celebrated industry.

Sources:

Kentucky Legislative Research Commission, “Catherine Spears Frye Carpenter (1760–1848)”, apps.legislature.ky.gov

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky Ancestors blog, “The Sour Mash Whiskey Recipe of Catherine Carpenter”, kentuckyancestors.org

Kentucky Historical Society Digital Collections, “MSS 47, Carpenter Family Papers” , kyhistory.com

Kentucky Historical Society Digital Collections, “Catherine Carpenter’s will”, kyhistory.com

Kentucky Historical Society, “Carpenter’s Station”, explorekyhistory.ky.gov

Contributed by Tracy McLemore, Fairview, Tennessee

Catherine Spears Frye Carpenters last will and testament left all her land and business holdings to her son George “Red Face” Carpenter

Some photos courtesy of the:

Kentucky Historical Society, 100 W. Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601