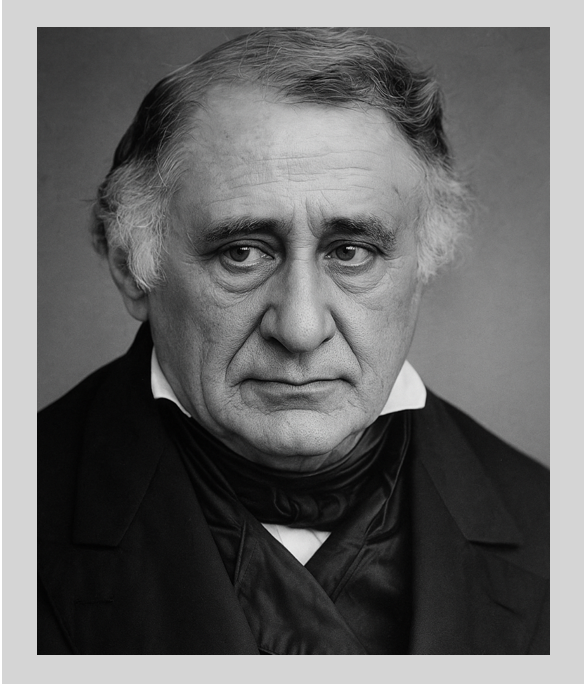

Abram Schwab

Above is an AI-enhanced image of Abram Shwab from a low-resolution photograph taken from the book “Manny Shwab and the George Dickel Company: Whiskey, Power and Politics During Nashville’s Gilded Age,” by Clay Shwab. The original photo was graciously provided by the Shwab family.

“The Wandering Merchant”

In the year 1817, in the rolling hills of Alsace, France, a boy was born into a world that offered him little welcome. His name was Abraham Schwab, though in time, as he crossed oceans and frontiers, he would often be known simply as Abram Shwab. He entered life in a corner of France that had long been caught between cultures, French and German, Catholic and Protestant, tolerant and hostile. For Jews like the Schwab family, the rules were especially clear: they could live in small villages, ply certain trades, and practice their faith quietly, but the gates of the great cities remained closed to them. From his earliest years, Abram learned resilience. His family’s modest livelihood revolved around a trade that Alsace knew well—wine. The boy apprenticed in the vineyards and cellars, not as a vintner but as a distributor. He grew into a young man with a keen eye for commerce, a respect for tradition, and a fire that persecution could not quench.

By the late 1830s, that fire led him to a decision. Napoleon’s restrictive laws still hung like chains over Jewish life in France. In 1839, Abram boarded a ship bound for America. He carried little more than a few contacts in the wine trade, a dogged faith in God, and a determination that his children would grow up in a land freer than the one he left behind. Two years later, in 1841, Abram became a U.S. citizen. He had already married Rebecca Hanauer, a fellow Alsatian Jew, around 1840, and together they began building the family that would accompany him through decades of movement, risk, and enterprise. Their first child, Cecelia, was born in 1842.

By the early 1850s, Abram’s compass pointed southward. Tennessee offered a growing market, particularly as towns like Knoxville and Nashville began to flourish. In 1853, the Shwabs made Nashville their home for a brief period, then shifted eastward to Knoxville in 1857.

As Abram worked to expand his enterprises, his children grew into their own stories. Cecelia, the eldest, became a bride at just fifteen. Her groom, Meyer Salzkotter, was her father’s thirty-four-year-old business partner, a match that handily combined personal with commercial ties, if not age compatibility. Notably, Cecelia and Meyer Salzkotter, despite Meyer’s great devotion to his pretty, young but impetuous wife, led a troubled and chaotic marriage for years, quarreling, outright divorcing, and then later remarrying at least twice.

By 1860, the Schwabs had dropped the “c” from their surnames and forged ties with entrepreneur George A. Dickel. With Abram providing capital, expertise, and European contacts, and Manny and Emile handling the energetic day-to-day operations, the partnership blossomed. Together, they laid the foundation of what would become George A. Dickel & Company, a name still synonymous with Tennessee whiskey.

The Civil War was a crucible for Abram Shwab. For merchants, wartime was both peril and opportunity. Nashville, seized by Union troops in 1862, became a hub of military logistics, where liquor was both contraband and commodity. Union officers enforced blockades, but demand for spirits remained insatiable. It was here that Abram Shwab and George Dickel revealed their ingenuity. False-bottom wagons rolled out of their Tennessee warehouses, laden with casks concealed beneath barrels of flour or crates of produce. What appeared to be legal provisions often carried contraband liquor, bound for officers and soldiers willing to pay a premium. The risks were real: confiscation, imprisonment, even ruin, but the profits built the fortunes that sustained both the Shwab and Dickel families well into the next generation.

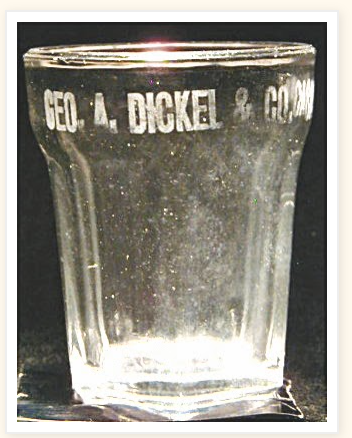

Gifts given to the best Cascade customers in the Dickel-Shwab-Salzkotter era included ceramic whiskey jugs and shot glasses, both of which are highly collectible today.

Despite his mercantile daring, Abram remained a devout Jew. In the South of the mid-19th century, Jewish life was sparse, scattered across small communities with few formal institutions. Abram longed to preserve the traditions of his ancestors and to give his children a spiritual home.

In time, his determination bore fruit: Abram helped establish Nashville’s first Jewish congregation. Ironically, an important and highly lucrative part of the Dickel-Shwab-Salzkotter business model was the Climax Saloon, which was in Nashville's prime entertainment district, close to the famous Maxwell House Hotel. The entertainment at Climax included liquor, gambling, and prostitution.

All of Abram Shwab's sons followed different paths. Joseph, the oldest boy, fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War, a decision that ended in tragedy when he was killed in battle. Harry and Emile, Shwab’s younger sons, as well as trusted son Victor “Manny” Shwab, all worked for Dickel; in fact, after Dickel’s death, Manny took control of the company, with the blessing of Augusta Dickel, George’s wife (and also Manny’s sister-in-law). The trio of Dickel, Salzkotter, and Shwab remained inextricably linked with each other and with Dickel’s Cascade Distillery throughout their lives. To that point, McLin Davis, who was the Master Distiller and part-owner of Cascade, had three sons, one of whom even married one of Abram Shwab's granddaughters in 1909.

Through the 1860s, Abram traveled tirelessly between Knoxville and Nashville, ensuring his businesses prospered. By the late 19th century, with Manny and Emile firmly established with Dickel, he began to withdraw from daily operations. On the threshold of the 20th century, Abram’s long journey came to its close. In 1900, at the age of 83, Abram Shwab died. In the end, he had provided the fledgling George A. Dickel company with startup capital, distribution expertise, including marketing, contacts, and principal labor in the form of his sons. To the generations that followed, he remained a figure of resilience and enterprise, a man who began in the vineyards of Alsace and ended as a mostly unknown patriarch of American commerce—an Alsatian Jew who had crossed an ocean, raised a family, defied prejudice, and left a huge imprint on both Jewish life and on Tennessee whiskey.

Sources:

Publication: “Manny Shwab and the George Dickel Company: Whiskey, Power and Politics During Nashville’s Gilded Age,” Clay Shwab, April 2024

genealogy.com, “Abraham (Abram) Shwab [Schwab]”

Chuck Cowdery blog, “The Lost Dickel Partner,” March 23, 2008

Those Pre-Pro Whiskey Men, “George Dickel…”, July 2, 2014

Contributed by Tracy McLemore, Fairview, Tennessee