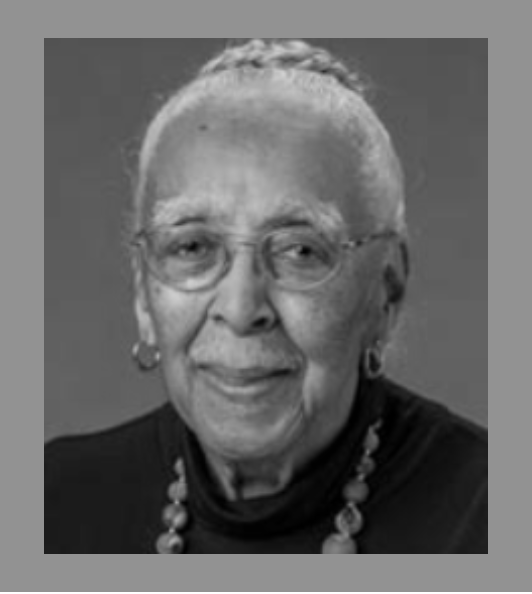

Elmer Lucille Allen

“Chemist Overcomer”

Elmer Lucille Allen (née Hammonds) was born on August 23, 1931, in Louisville, Kentucky, and grew up in the Russell neighborhood of West Louisville. Her parents, Ophelia and Elmer Johnson Hammonds, raised three children: Elmer Lucille, her younger brother (also named Elmer), and her baby sister, Mary Elizabeth. To avoid confusion between the three Elmers in the home, the Hammonds’ affectionately nicknamed their oldest daughter “Cile.”

From childhood, Cile showed both drive and imagination. At just nine years old she sold the most cookies in her Girl Scout troop. Her early but talent-rich artwork, signs of the creativity that would later define her, appeared in the local newspaper that same year. Cile also excelled academically at Western Elementary and Madison Junior High, where a seventh-grade sewing class planted a seed that would later flourish into her life in the arts. She graduated from Central High School in 1949, but getting there had required courage: throughout her school years, Cile battled a persistent stutter. Under the guidance of her English teacher, she spent hours practicing speaking in front of a mirror training herself to pronounce each word with deliberate clarity. Her determination carried her all the way to the high-honor distinction of delivering Central High’s commencement address, which she accomplished without a trace of a stutter. After high school, Allen enrolled at Louisville Municipal College, an all-black branch of the University of Louisville. When LMC closed two years later, Elmer transferred to Nazareth College. She later reflected that it was not until she was a junior at Nazareth that she attended school alongside white students for the very first time ever.

At Nazareth, Allen majored in chemistry and minored in mathematics, graduating with her Bachelor of Science in 1953. But Louisville’s job market offered few scientific opportunities for Black women, even for ones as bright as Cile Hammonds. Undeterred, she moved to Indiana, passed a civil-service exam, and began working as a clerk-typist at Fort Benjamin Harrison. Soon restless in clerical work, she returned to school to become a certified Medical Laboratory Technician and secured a position at Indianapolis General Hospital. Around 1958, homesickness drew her back to Louisville, where she found work at both Children’s Hospital and then at the University of Louisville conducting medical and dental research for six years.

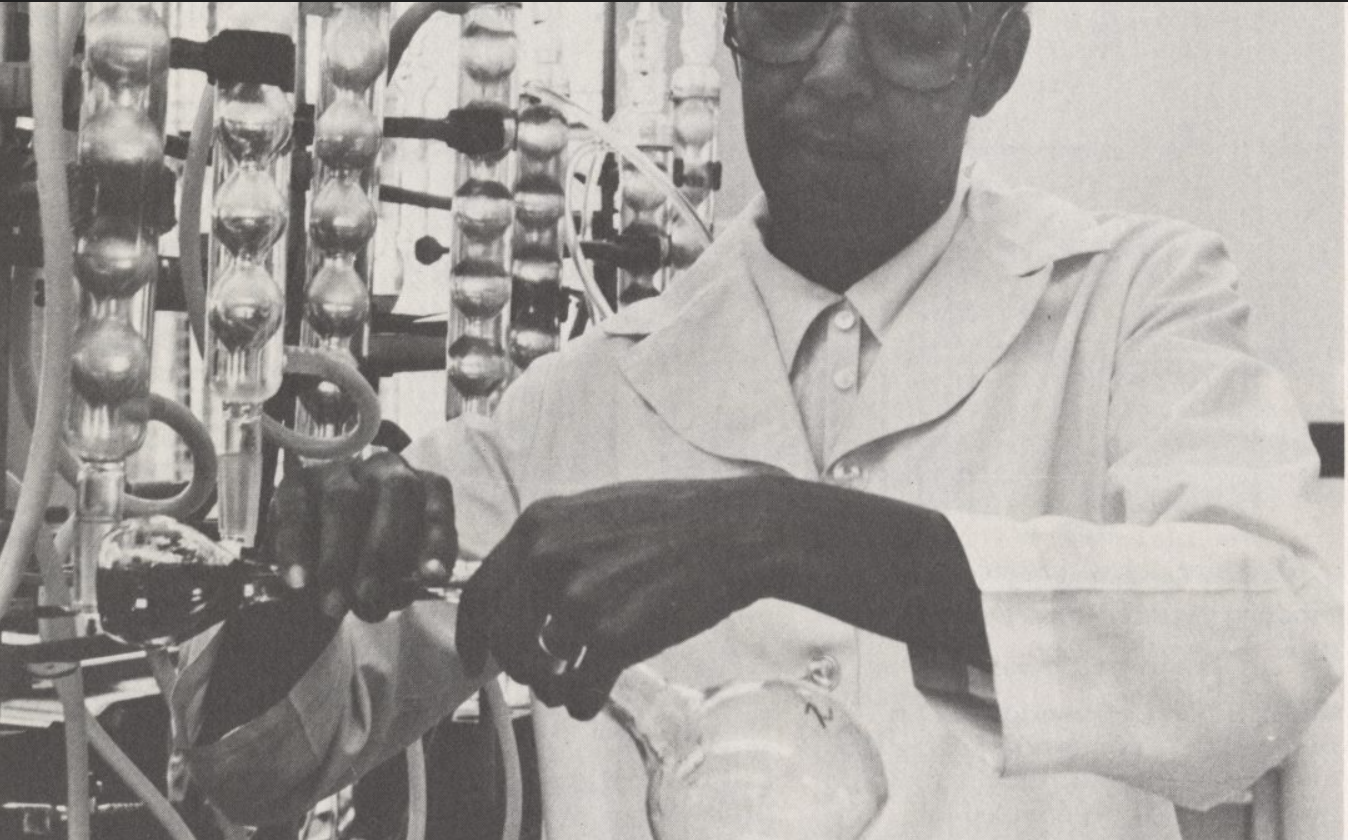

Allen’s career took a transformative turn in April 1966 when she applied for a job at Brown-Forman, the Louisville-based spirits company that had, with its then-recent purchase of Jack Daniel’s, become a big name in American whiskey. Her hiring was historic: she became Brown-Forman’s first African-American chemist, and one of the very few women working anywhere in the company outside secretarial roles. Brown-Forman in the late 1960s was a smaller, family-run environment, but its laboratory demanded rigorous scientific work. Allen’s responsibilities placed her at the heart of whiskey production. She analyzed the chemical composition of the raw grains, corn, rye, and malt, that formed the backbone of the company’s bourbons. Her work ensured that every batch of grain met strict quality and consistency standards, effectively safeguarding the integrity of legendary Kentucky brands such as Old Forester and Early Times.

Beyond grain analysis, Allen helped evaluate other inputs and processes involved in distillation, fermentation, and maturation. Her work contributed to the development and maintenance of the company’s internal quality controls during a period when the American whiskey industry was evolving in both scale and scientific sophistication. In a male-dominated laboratory culture, Allen’s precision, reliability, and professional demeanor earned her deep respect. But her role also represented a powerful breakthrough. At a time when color barriers still shaped most American workplaces, Allen’s presence in a white-collar laboratory was uncommon, to say the least, in Louisville’s industrial and scientific sectors. Colleagues later recalled that Allen had consistently carried herself with calm authority, professionalism, and integrity, setting a model for future generations of, not only minority chemists, but all of her co-workers.

Allen working in Brown-Forman’s lab in the 1970s

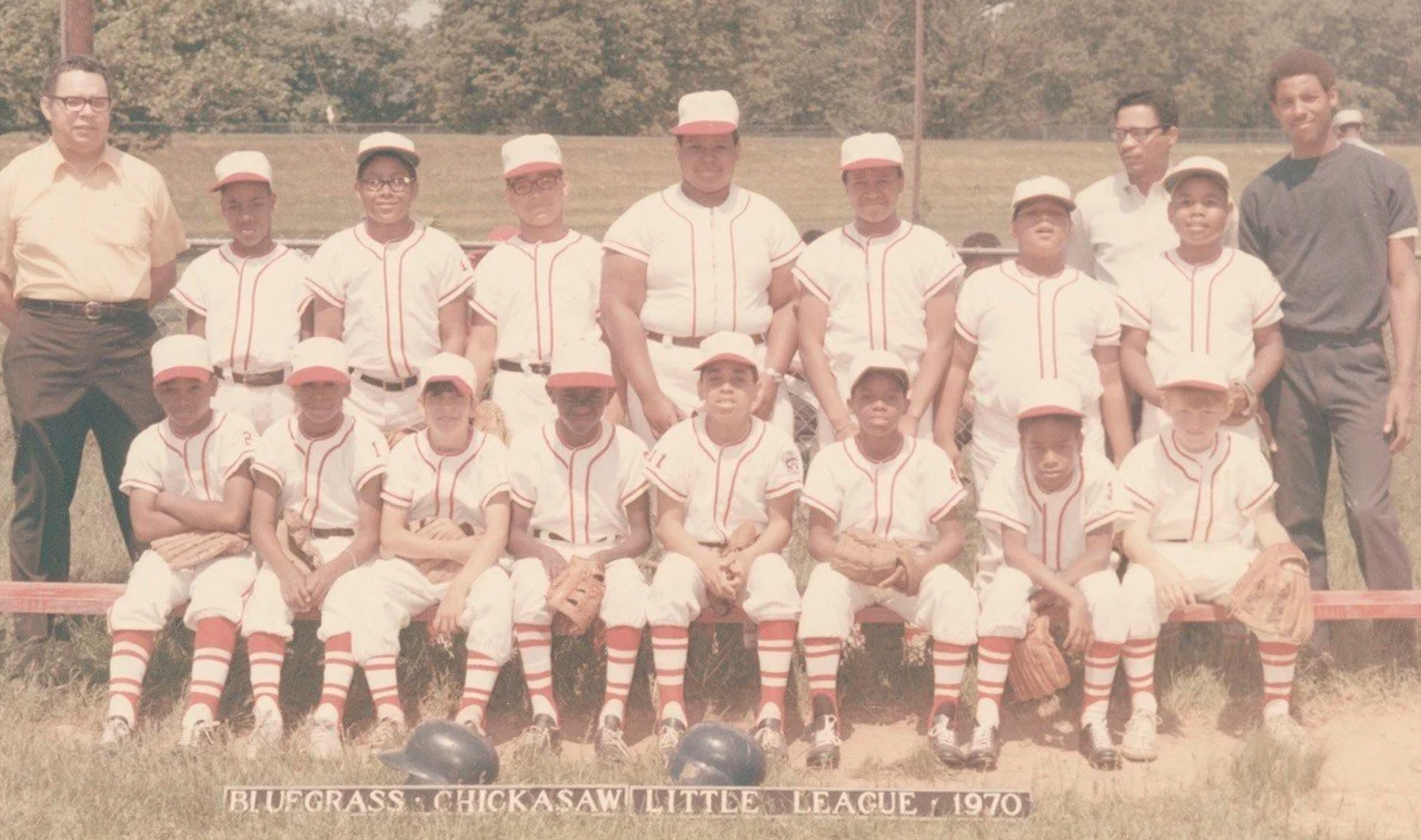

Brown-Forman also shaped her personal life, for it was there that, in 1968, Elmer met her life-partner and future husband, Roy Allen. The two soon wed and built a full, active life together, raising three children while both working full time. Even as her scientific career progressed, Allen stayed committed to community work. In 1969, she and Roy founded the Chickasaw Little League after their son was unable to join a segregated baseball team in their neighborhood. The new, integrated league began with six teams and welcomed children of all races, becoming a significant step forward in local youth sports inclusivity.

In the 1980s, Elmer co-founded the Kentucky Coalition for Afro-American Arts, and served as its president for a decade. Her own interest in the arts had never faded; she had loved crafts since childhood, but it was a ceramics class she took after her youngest child left for college that revived her passion. Originally, she took the class to help relieve arthritis in her hands. Instead, it opened an entirely new creative world. So, beginning in 1981, Elmer enrolled in ceramics courses at the University of Louisville, eventually developing the distinctive porcelain reduction-fired boxes and stenciled wall hangings that would become her signature.

In the 1980s, Elmer co-founded the Kentucky Coalition for Afro-American Arts, and served as its president for a decade. Her own interest in the arts had never faded; she had loved crafts since childhood, but it was a ceramics class she took after her youngest child left for college that revived her passion. Originally, she took the class to help relieve arthritis in her hands. Instead, it opened an entirely new creative world. So, beginning in 1981, Elmer enrolled in ceramics courses at the University of Louisville, eventually developing the distinctive porcelain reduction-fired boxes and stenciled wall hangings that would become her signature.

In the 1980s, Elmer co-founded the Kentucky Coalition for Afro-American Arts, and served as its president for a decade. Her own interest in the arts had never faded; she had loved crafts since childhood, but it was a ceramics class she took after her youngest child left for college that revived her passion. Originally, she took the class to help relieve arthritis in her hands. Instead, it opened an entirely new creative world. So, beginning in 1981, Elmer enrolled in ceramics courses at the University of Louisville, eventually developing the distinctive porcelain reduction-fired boxes and stenciled wall hangings that would become her signature.

After 31 years at Brown-Forman, Allen retired in 1997 at age 66. Retirement, however, simply meant the start of another chapter. She returned to the University of Louisville and earned her Master of Arts in Studio Arts. Her thesis exhibition featured more than 200 ceramic works, demonstrating a breathtaking artistic range that blended scientific precision with expressive form. In the decades that have followed, Allen has emerged as a celebrated figure in Louisville’s cultural world: an exhibiting artist, mentor, community advocate, and champion for women artists and artists of color. Her dual identity as both scientist and artist made her an inspiring model for younger generations exploring interdisciplinary work.

Elmer Lucille Allen poses with two of her fiber artworks at the Frazier museum at the age of 92, April 10, 2022.

Photo courtesy of Brett Eugene Ralph

In many ways, her name predicted her path. “Elmer Lucille,” a traditionally masculine first name paired with a feminine middle name, reflected the duality of her life: a woman succeeding in traditionally male spaces, forging her own identity in science, community leadership, and art. Her story is not only about breaking boundaries in a segregated era; it is about relentless curiosity, resilience, and the power of a calm, steady presence to change institutions.

As of 2025, at age 94, Elmer Lucille Allen remains active in mentoring others, still offering encouragement, wisdom, and guidance to anyone who seeks it. Her legacy bridges scientific achievement, artistic brilliance, and decades of community activism. She stands as a true Louisville icon: a woman who proved that talent and determination can reshape and improve the worlds of chemistry, culture, and whiskey.

Sources:

University of Louisville, “Elmer Lucille Allen”, Louisville University Women’s Center, Community Pearls of Kentucky, louisville.edu

Bourbon Women Association, “…Brown-Forman Retired Chemist…”, May 10, 2021

American Whiskey Magazine, “90 Years of Elmer Lucille Allen”, November 8, 2021

WLKY-TV (Louisville, Kentucky), “Louisville woman recognized as first Black chemist at Brown-Forman distillery”, Jamie Mayes, September 1, 2023

WDRB-TV (Louisville, Kentucky), “Trailblazing bourbon chemist celebrated with street sign in Louisville”, Aug 23, 2025

San Diego Squared, “Elmer Lucille Allen: Chemist, Artist, and Lifelong Learner”, sd2.org

Black Cultural Center Virtual Museum (Artist Bio), “Elmer Lucille Allen”, purduebcc.omeka.net

Some photos courtesy of Frazier Museum via E.L. Allen. Some photos courtesy of bourbonwomen.org

Contributed by Tracy McLemore, Fairview, Tennessee