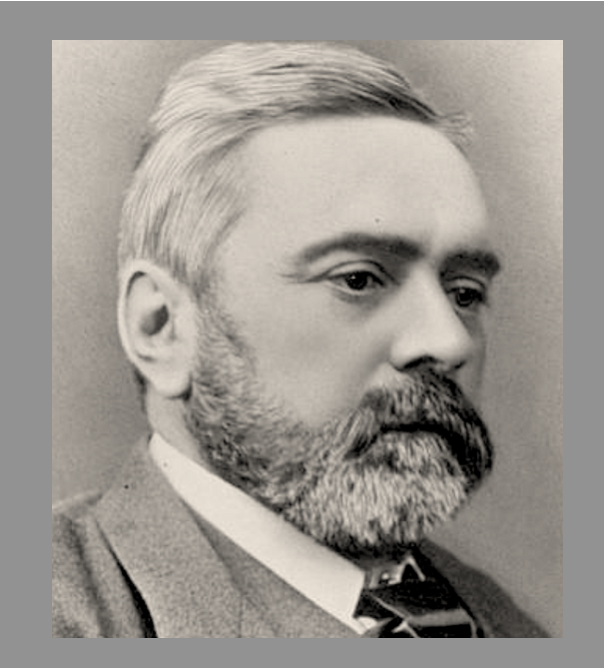

Alexander Walker

Alexander Walker (often called Alec) was born in Kilmarnock, Scotland, on 10 February 1837, into a family business that was already learning how to make whisky behave like a dependable product instead of a charming gamble. At the time, his father, John “Johnnie” Walker, ran a grocer’s shop on Kilmarnock’s High Street. The store was a typical nineteenth-century store where tea, spices, wine, and spirits shared shelf space, and where customers expected the grocer to stand behind everything he sold. When his single malts varied so very greatly from cask to cask, Johnnie’s solution was that he blended. So by the time Alexander was a boy, the Walkers’ name was tied not only to retail trade, but to a growing reputation for a whisky that tasted not only great, but “the same” from one purchase to the next.

Johnnie Walker and his wife Elizabeth had other children—Elizabeth, John, Robert, and Margaret—but it was Alec who would become the central heir to the whisky side of the business. He grew up in a town being reshaped by new logistics. The railway arrived in Kilmarnock in 1843, and suddenly the business horizon widened beyond the pace of horses and carts. Soon the store’s wares, especially the whisky, moved—quietly at first, then in volume.

The family nearly lost everything in 1852, when a flood destroyed the Walkers’ stock. For a young Alec the lesson was blunt: even a good business can be broken by one bad day. When the operation recovered, it did so in an era that rewarded people who could think in systems in terms of supply, storage, repeatable quality, distribution routes, and brand recognition.

Alec officially joined the family business in 1856, stepping into work that combined the ordinary discipline of shopkeeping with the more specialized craft of selecting, marrying, and selling whisky. Tragically, the following year of 1857, Johnnie Walker died, leaving Alec in charge of the entire operation at only twenty years of age. What he inherited was not a romantic “distillery” story so much as a practical commercial engine: customers, relationships with suppliers, and a product that could be scaled, providing the right choices were made. Those choices began with export thinking. In the early 1860s, Alec pushed the Walker whisky trade outward, and treated shipping not as a barrier but as a sales channel. One of his smartest decisions was packaging, because the container often decides whether the contents survive. In 1860, he introduced the square-sided bottle for Walker’s whisky. It was a functional idea with brand consequences: square bottles packed tighter, broke less, and made it easier to send whisky farther with fewer losses. Just as important, a bottle shape is a kind of signature. Even before the label was read, the form could be recognized.

The timing also favored ambitious blenders. The Spirits Act of 1860 helped enable large-scale blending in bond, making it easier for businesses like the Walkers’ to operate at an industrial pace. Alec’s work was not simply “more whisky,” but a more modern whisky business: one that was built on repeatability and a recognizably branded product.

By 1862, Walker whisky sales were reported at 100,000 gallons (about 450,000 litres) per year, a figure that signals how quickly the firm was moving from local success to something like a national, nay an imperial, presence. Yet Alec still needed a product identity that could travel as well as the liquid itself.

That identity sharpened when in 1865 Alec created a blend called “Old Highland Whisky,” and in 1867 it was formally registered, placing it among the earlier whisky brands to be protected in that way. This was a crucial shift: a consistent blend could be more than a shop specialty, it could be a named thing that buyers requested and that competitors could not easily imitate without being obvious.

Alec’s personal life was developing alongside the brand. He married Georgina Paterson on 30 April 1861. Their family life abruptly carried both joy and loss, however, when their son George Paterson Walker was born on 15 October 1864, but Georgina died two weeks later, leaving Alec a widower with a newborn while his business was still expanding at speed.

About two years later, Alec married Isabella McKemmie. Their children included Alexander Walker II, who was born 22 March 1869. Alexander II was the son who would later become one of the best-known Walker leaders, though daughters Helen (born 1870) and Isabella (born 1872) also played their parts in the business as adults.

While those family milestones were unfolding, Alec continued to refine the visual “tell” of Walker whisky. In 1877 the slanted label was trademarked, set at 24 degrees, a deliberate angle that made the bottle stand out and created more usable label space without changing the bottle. It is hard to overstate how modern this thinking was. Alexander treated the label not as decoration but as a practical tool—an early form of shelf strategy—at a time when many whisky sellers still behaved like local merchants rather than brand builders.

By 1880, Walker whisky had begun winning formal recognition; the brand won a medal at the International Exhibition in Sydney in 1879, another marker that the business was operating on a global stage rather than merely shipping outward from Scotland. Behind the scenes, the work remained intensely methodical: maintaining stocks, keeping a blend consistent, and ensuring the business could survive shocks like supply problems, economic swings, or the simple unpredictability of taste.

Alexander “Alec” Walker died on 16 July 1889, only 52 years old, and control of the firm passed to his sons, George Paterson Walker and Alexander Walker II, who divided responsibilities between business/marketing and production/blending. The “Striding Man” and the now-familiar Red/Black naming system would come later, but they were additions to a structure Alexander had already designed: a whisky meant to be recognized, requested, shipped, and trusted.

If Johnnie Walker’s gift was discovering that blending could turn inconsistency into reliability, his son Alexander’s gift was proving that reliability could be scaled without losing its identity. He took a family grocer’s whisky and gave it the infrastructure of a modern brand: protective packaging, protected names, and a label that could announce itself from across a room. By the time he was gone, the Walker business was no longer simply a Kilmarnock success story. It was a system built to travel, and one that has now done so readily for more than 160 years.

Sources:

The Whisky Exchange, “Johnnie Walker History”, thewhiskyexchange.com

Johnnie Walker official website, “The Johnnie Walker Story”, www.johnniewalker.com

Mark Littler, Ltd., “Johnnie Walker: A History…”, Hannah Thompson, 05 October 2023

FamilySearch, “Alexander Walker, Sr.”, ancestors.familysearch.org

The Minters Exchange, (genealogy site), “Georgina Paterson”, theminters.co.uk

Contributed by Tracy McLemore, Fairview, Tennessee USA